Embracing Plotlessness

How the rootling place wants to help you wander

ROOTLING/The rootling place is a website for learning about pigs, but also for performing a different approach to doing research.

Rootling on this website is more than scrolling, which we regard as aimlessly drifting through algorithmically curated content leading to an experience of pacification. The website interface instead aims to scaffold a more engaged approach to online wandering. While you initially might not be able to make sense of how this website is organised or know precisely what to do when you arrive: you just need to be curious enough to explore.

An interest in pigs might help you to be persistent and spontaneous - to scroll and swipe playfully with "a lightness of heart, a glint in the eye, alertness, enthusiasm and readiness for surprise".1 Taking interest in and touching or clicking on the shimmering objects onscreen are exploratory acts and curious gestures that aim to (re)discover the familiar yet underappreciated animal.

Our concept of rootling-as-research and the interface of ROOTLING/the rootling place were informed by how we/the sounder resonated with the thorough, passionate, and open-ended process by which pigs explored the diverse social and material opportunities in an environment. We were struck by how their fluid engagement with the world eluded human orders and expectation.

The book cover of Wallace the Wandering PIg by Judy Van de Veer

Interestingly, the term "rootling" in colloquial British English is also adapted to describe human behaviour. This version refers to a haphazard mode of searching among a mess of things2 and so implies this activity shares similar qualities with pigs. However, a literal pig snouting and digging up food, while fluid and exploratory, is not as disorganised or random as this figurative comparison suggests. Admittedly, our perceptual limitations mean that when observing a pig, we are not able to follow the patterned scent and delicious taste of substrates that guide the nonhuman's search, nor their decisions as to why they rootle here and not there.

To facilitate free-ranging inquiry without suggesting complete aimlessness, the website's interface deliberately fosters open-endedness while maintaining some minimal forms of structure: There are limited discernible anchors in the landscape, apart from its risky frayed edges and the ROOTLING entries which form a patterned axis to help spatial orientation; The entries are often arranged randomly, although in some locations they cluster themselves meaningfully; There are limited shortcuts and no search functions, but there is the option to select tags if you develop a topical interest - tags serve as an analogy to a porcine scentscape that enables rootlers to follow certain tastes.

Losing the plot

As you dig, follow links, find and escape dead ends, new ideas might take root, and the meaning of a pig might emerge over time. As you rootle, free yourself from concerns about consistency, time, or a final outcome. There is no grand narrative or conclusive statement about pigs to be found. Exploration is yours, as you wish and feel.

In part, ROOTLING/the rootling place expresses what Synthia Sydnor and Robert Fagan refer to as “plotlessness” in ethnography.3

Plotlessness in its various forms is familiar to many social researchers. Doing ethnography demands bodily, cognitive and emotional discipline and rigorous documentation; yet it can often also involve being clueless: “stumbling, making mistakes, getting sidetracked, being surprised, wasting time, and failing.” 4. Archival research involves methodical perseverance and attention to detail; yet can also be punctuated and made successful through the chance encounters which enable the “flight of imaginative experience”5 and “affective experience of wonder.” 6

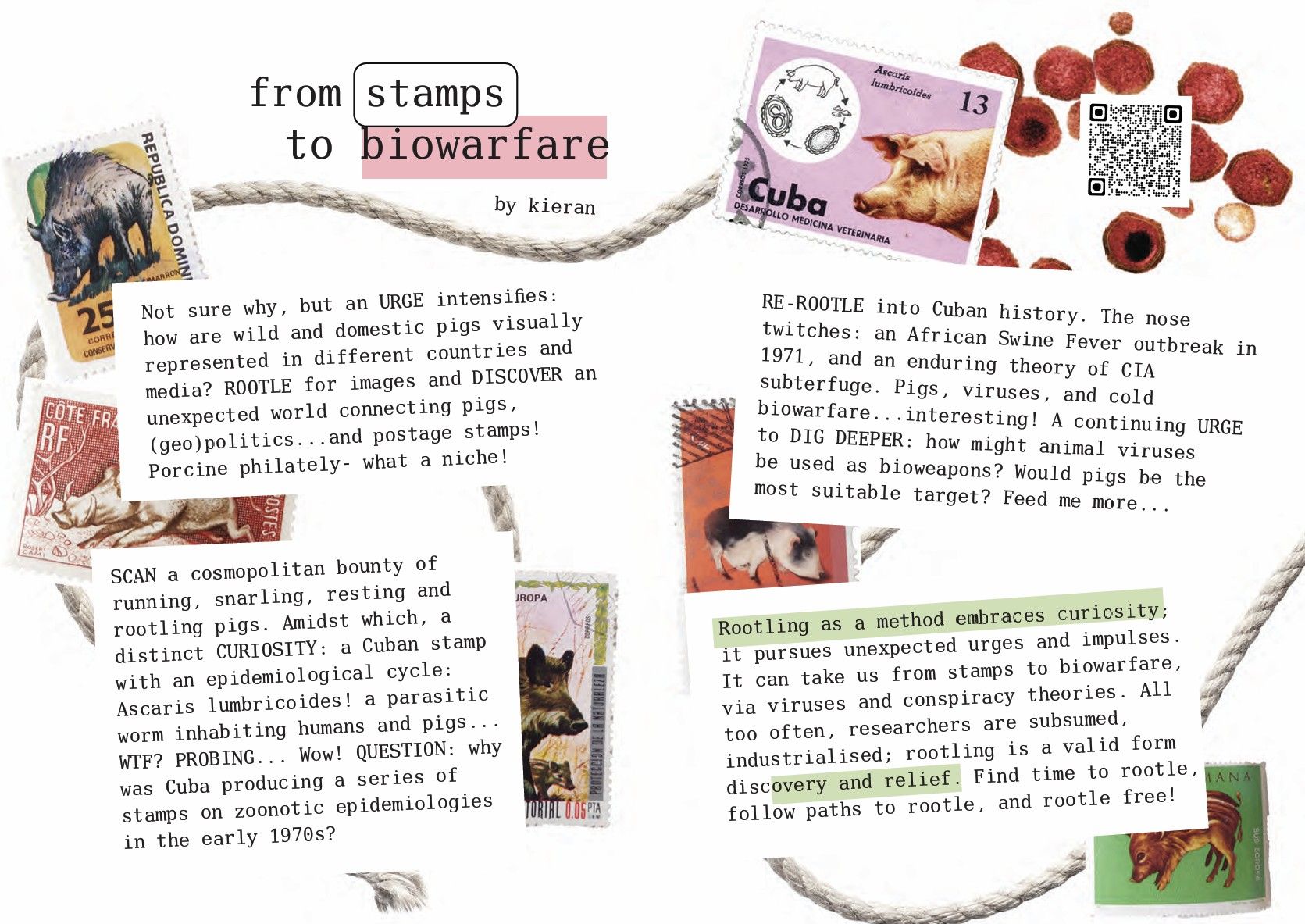

Kieran O'Mahony gives an autobiographical example of rootling as research, attending to shifting affects and unexpected routes. From ROOTLING ZINE

Ethnography and archival research can be planned, but when conducted do not necessarily follow a singular or linear pathway. In the case of ethnography, key research questions might change or initially be undisclosed, methods can be fluid and developed in situ, and there are no guarantees of logical explanations or take-home stories.7 Insight can emerge as accidental outcomes or ‘aha’ moments, rather than an effect of a prescribed sets of steps. Plotlessness, to a degree, requires sometimes letting go of the pretentions of routinised production and allowing yourself to become vulnerable and swept up in unplanned directions. Dissaray, in this instance, can be a creative act.

While research is formally presented as controlled and directed, in reality it can be a messier and more non-linear process than we would like to admit - this is as true across both the social and natural sciences. 8 So, why not embrace this plotlessness in our writing, and keep ourselves open to the possibility of a more playful (and potentially more accurate) mode of representation? We (like Syndor and Fagan who quote him) adhere to Norman Denzin’s inspiring proclamation for:

an unruly ethnography fractured, a mosaic of sorts, layered performance texts, messy, a montage, part theory, part performance, multiple voices. . . . A critical performance ethnography that makes a difference in the world. 9

Similarly, this website is a critical performative piece designed to reflect our own unruly pathways when learning about human-pig relations. It is a bricolage of knowledges, styles, and possibilities, together constituting the idea of a pig that is incomplete and forever taking shape.

ROOTLING/The rootling place asks you – the rootler – to find time to adopt the spontaneous trajectories and omnivorous appetites that we have also enjoyed. By enacting this method through an virtual environment, we take advantage of the productive plotlessness that can be inherent mode of surfing the internet. As anthropologist Daniel Miller reflects in his research on Trinidadian websites, 10 he would begin on a particular route of investigation and then finally be seduced into other directions...

often to such a degree that it was hard to retrieve the original place from which this diversion had begun, but often grateful that my lack of determination had in fact led to me to view some unexpected vistas and delight in some other creations than those I would otherwise have encountered.

Likewise, we hope your concept and horizons of pigs and human-pig relations are expanded by rootling through the unexpected entries on this website, regardless of whether you do (or do not) find valuable reflections on your research practices in the process.

Prizing playful pathways

While not disregarding the need for structure and method, we created the rootling place to better foreground the nourishment of discovery and the joy of uncertain journeys. It aims to show that learning also needs to be a creative and experimental process through which we accrue and consolidate interests. It demonstrates that reading and thinking needs the time and space to meander, to dwell, and to be unstructured. Rootling welcomes wonder and frivolousness into the all-too-serious academic work.

Illustration by Paul Gladone from The Three Little Pigs - he also illustrated Wallace, the Wandering Pig. The text has been modified.

When scholars and educators try to rationalise and instrumentalise play, it often frustrates because it lacks clear plotlines, simple explanation, and productive ends 11. This poses problems in an academic environment where metrics, outputs and tangible impacts are prized over processes. Even critical practices such as reading are required to become focused, purposeful, and extractivist. Is there time and space to learn playfully, and to research plotlessly?

Hopefully, the existence of ROOTLING/the rootling place suggests yes! It is a space that not only invites critique of pig-hostile worlds, but also neoliberal work environments and simplified academic practice.

That being said, as early career researchers supported by a well-funded EU project, we acknowledge the privilege that enabled us/the sounder to develop the rootling place. This financial and temporal freedom allowed us to explore practices that might otherwise be considered too experimental or unproductive within conventional academic structures. Learning playfully and plotlessly may not be accessible for everyone.

Despite recognising this privilege, we remain ambivalent: we are still subject to pressures to produce measurable outputs and enhance our academic profiles. While we were lucky to have the time and funds to find release in developing the rootling place, as junior scholars we are also acutely aware that this project will likely elude contemporary ways of assessing the research value and its impacts.

Footnotes

-

Gordon, G. 2009. "What is play? In search of a definition." In D. Kuschner (ed.) From children to red hatters: Diverse images and issues of play,(1-13). Lanham: University Press of America. ↩

-

Given it is etymologically connected to wroten in middle English, which can refer to a pig digging with a snout, rootle was a term evidently adapted to describe humans, ↩

-

Sydnor, S. & Fagen, R. 2012. "Plotlessness, ethnography, ethology: play." Cultural Studies? Critical Methodologies, 12(1): 72-81. ↩

-

p. 212, Günel, G., Watanabe, C., Jungnickel, K. & Coleman, R., 2023. "Everything is patchwork! A conversation about methodological experimentation with patchwork ethnography." Australian Feminist Studies, 38(115-116): 211-229. ↩

-

Tamboukou, M. 2016. "Feeling narrative in the archive: the question of serendipity." Qualitative Research, 16(2): 151-166. ↩

-

Gulledge, J. 2024. "People in Drawers: Finding Wonder in the Archives." Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 67(4):.566-576. ↩

-

Sydnor, S. & Fagen, R. 2012. "Plotlessness, ethnography, ethology: play." Cultural Studies? Critical Methodologies, 12(1): 72-81. ↩

-

Law, J. 2004. After Method: Mess in social science research. Routledge: London. ↩

-

see p. 77, Sydnor, S. & Fagen, R. 2012. "Plotlessness, ethnography, ethology: play." Cultural Studies? Critical Methodologies, 12(1): 72-81. ↩

-

Miller, D., 2000. "The fame of Trinis: websites as traps." Journal of material culture, 5(1), pp.5-24. ↩

-

Sydnor, S. & Fagen, R. 2012. "Plotlessness, ethnography, ethology: play." Cultural Studies? Critical Methodologies, 12(1): 72-81. ↩